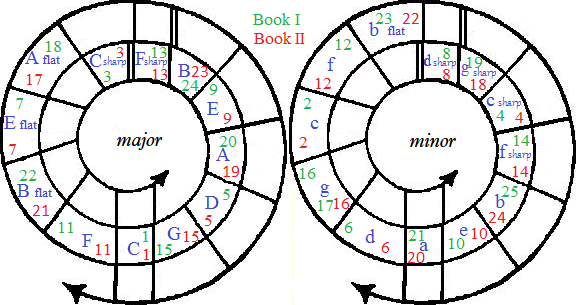

The preludes and fugues from Das wohltemperierte Klavier in the circle of fifths.

To the foundations of the edifice of music, Johann Sebastian Bach contributed huge blocks, firmly and unshakably laid one upon the other. And in this same foundation of our present style of composition is to be sought the inception of modern pianoforte-playing. Outsoaring his time by generations, his thoughts and feelings reached propertions for whose expression the means then at command were inadequate. This alone can explain the fact, that the broader arrangement, the “modernising”, of certain of his works (by Liszt, Tausig, and others) does not violate the “Bach style” – indeed, rather seems to bring it to full perfection; – it explains how ventures like that undertaken by Raff, for instance, with the Chaconne* are possible without degenerating into caricature.

Bach's successors, Haydn and Mozart, are actually more remote from us, and belong wholly to their period. Rearrangements of any of their works in the sense of the Bach transcriptions just noticed, would be sad blunders. The clavier-compositions of Mozart and Haydn permit in no way of adaptation to our pianoforte-style; to their entire conception the original setting is the only fit and appropriate one.

The spirit of Mozart's piano-style is handed down, in a form internally weakened but externally enriched, by Hummel. With the latter begins that phase of musical history which deserves to be termed “feminine”, wherein Bach's influence, and consequently his connection with the composing virtuosi of the pianoforte, grows weaker and weaker – parallel with the comprehension of these gentlemen for Bach's music.

The unhappy leaning towards “elegant sentimentality”, then spreading wider and wider (with ramifications into our own time), reaches its climax in Field, Henselt, Thalberg and Chopin**, attaining, by its peculiar brilliancy of style and tone, to almost independent importance in the history of pianoforte-literature.

But with Beethoven, on the other hand, new points of contact with the Master of Eisenach were evoked, bringing the advance of music nearer and ever nearer to the latter; nearest of all in Liszt and Wagner***, the characteristics in the style of either pointing directly Bach-ward, and completing the circle which he began. The attainments of modern pianoforte-making, and our command of their wide resources, at length render it possible for us to give full and perfect expression to Bach's undoubted intentions.

It therefore seemed to me the proper course to pursue, to begin with a digression from the “Well tempered Clavichord” – a work of so high importance for the pianoforte and of such comprehensive musical value –, that I might trace and show (from the very trunk, as it were) the manifold outbranchings of modern pianoforte-technic.

Although we owe to Carl Czerny – a man whose importance is derivable in no small measure from the fact, that he forms the intermediate link between Beethoven and Liszt – the resurrection, so to speak, of the “Well tempered Clavichord”, this admirable pedagogue handed us the work in a garb cut too much after the fashion of his period; hence, neither his conception nor his method of notation can pass unchallenged at the present time. Bülow and Tausig, advancing on the path opened by the revelations of their master,

* This piece, originally written by Bach for solo violin, was arranged by Raff for full orchestra.

** Chopin's puissant inspiration, however, forced its way through the slough of enervating, melodious phrase-writing and the dazzling euphony of mere virtuose sleight-of-hand, to the height of teeming individuality. In harmonic insight he makes a long stride toward the mighty Sebastian.

Mendelssohn's “Hummelized” piano-style, overflowing with smoothly specious counterpoint, has naught in common with Bach's rock-stirring polyphony, all earlier and persistent arguments to the contrary notwithstanding. On the other hand, Mendelssohn's successful effords to inaugurate performances of Bach's works, must be set down as redounding to his credit.

*** The truth of this assertion, as regards Liszt, shows most clearly in his magnificent Variations on a motive from Bach (“Weinen, Klagen”), and in the Fantasia and Fugue on B,A,C,H.

Conversely, the recitatives in Bach's Passions stand nearest, among all classico-musical productions, to Wagner's spirit, both in respect to their expressional form and depth of feeling. [Comp. Note 3 to Prelude VI]

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Liszt, by his interpretations of the classics, were the first to attain to fully satisfactory results in the editing of Bach's works. This is abundantly proved, in particular, by Bülow's masterly edition of the Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue, and Tausig's Selection from these Preludes and Fugues.

Much will be met with, in the course of this work, which substantially agrees with Tausig; but identical passages are rare. In this connection I beg to quote from a letter written by the poet Grabbe to Immermann concerning a proposed translation of Shakespeare: “Where I could use Schlegel”, he writes, “I did so; for it is ridiculous, stupid, or vain in a translator to leap aside over hedges and ditches, where his predecessor has made a path for him”.

The need of an edition as complete* and correct in form as possible has induced the editor, in this attempt to furnish such an one, to bestow upon his work the most painstaking and conscientious attention, reinforced by more than ten years study of this particular subject. The present edition, however, also aims in a certain sense at re-founding, as it were, this inexhaustible material into an advanced method, on broad lines, of pianoforte-playing; this aim will, however, be carried out principally in Part. I, that being preponderant in the variaty of its technical motives.**

The present work is also intended as a connecting link between the editor's earlier edition (publ. By Breitkopf and Härtel) of Bach's Inventions, forming on the one hand a preparatory school, and his concert-editions of Bach's Organ-fugues in D and E flat, and the Violin-Chaconne, which will serve, on the other hand, as a close to the course herein proposed.

Following these last, the study of further pianoforte-arrangements of Bach's organ-works is recommended, namely:

Liszt, Six Preludes and Fugues.

Fantasia and Fugue, G-minor.

Tausig, Toccata and Fugue, D-minor.

D'Albert, Passacaglia.

When these works have been thoroughly learned, both musically and technically, every really ambitious student of the piano ought to take up the still unarranged organ-compositions of Bach, and try reading them at sight with as great completeness and richness of harmony as is possible on the pianoforte (doubling the pedal-part in octaves wherever feasible). The manner in which this is to be executed, is suggested in the Examples of Transcription given as an Appendix to Part I.

Still, this comprehensive course of study in Bach's piano-music forms but a part of that which is necessary to make a thorough pianist of a person naturally gifted. If this truth were stated in plain terms by every conscientious teacher to zealous beginners, the standard wherewith people are now-a-days content to compare the artistic and moral capacities of students would speedily be raised to a height inconveniently beyond the reach of the generality. By such means a barrier might gradually be built up against dilettantism and mediocrity, and thus against the degeneration of art, – a barrier which might cause many to pause and reflect, more carefully than present conditions render needful, before risking a leap and a possible breaking of their necks.

Tausig unfortunately left the greater half of the work untouched, several keys being unrepresented in his Collection; even the monumental B flat-minor fugue in Part II (to mention one instance) is omitted; neither can he escape the censure of having reproduced certain incorrect readings of the Czerny text. – Bischoff's and Kroll's praiseworthy efforts were confined for the most part to a critical textual revision. Recent good editions are those by Franz and Dresel, Louis Köhler, Jadassohn, Reinecke and Riemann. The chief aim of this last revision is analytical phrasing and anatomization. Analyses in book-form have also been published by Riemann and still earlier by van Bruyck.

** The editor does not for a moment imagine that he is able to exhaustively accomplish this task alone. He will be well satisfied if he should succeed in disclosing a broader horizon for the study of Bach's works, and in formulating a plan for successfully bridging over the interval between the “Well tempered Clavichord” and modern piano-technic.

New York, January, 1894. Ferruccio B. Busoni.

Copyright © 2014 Inno de Linnep webmaster@delinnep.com